We Have to Rethink Human Rights, Part 1

How would you react if I told you that 'universal human rights' are not actually universal at all, but rather a cleverly packaged Western export that has often done more harm than good? And that embracing multiple, even different frameworks could actually strengthen human dignity worldwide?

We know we have to shift our mindsets in this liminal space, during this time of transition from what was, to what is still to come. One of the shifts that are most essential is how we conceptualise and assess human rights.

This will have enormous implications for our emerging multipolar world.

Even if we are not prepared to change our own perspectives, we have to engage respectfully with the views of others, with nuance, with sensitivity, as I will explain in Part 2.

Recognising the Pattern

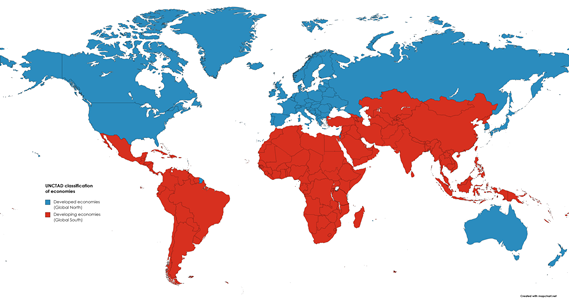

For decades, we have watched with bemusement and often with horror as human rights were wielded selectively, and weaponised by those in power - condemning China's governance while arming Saudi Arabia's absolute monarchy, decrying authoritarianism in Venezuela while bankrolling Egypt's military government, wringing hands over Xinjiang or Ukraine while funding Israel's occupation and more recently, slaughter of helpless civilians.

The pattern is too consistent to ignore. As former Singaporean Foreign Minister George Yeo observed, quoting another: "Americans are not known to love Chinese, and they're not known to love Muslims. But somehow they love Chinese Muslims a lot."

The hypocrisy is not subtle. But it is strategic.

What should really trouble us is that this selective enforcement of the term, and the overwhelming rhetoric around it, obscure something deeper. The entire framework of 'universal' human rights emerged from post-war Western Europe and America, rooted in Enlightenment individualism and liberal political theory.

It prioritises civil and political freedoms - speech, assembly, voting - while treating economic and social rights as secondary concerns.

But just watch a mother's face in rural Bangladesh, DRC or Bolivia when you tell her that free speech matters more than feeding her children.

The Story You Never Heard

During the 1948 drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), China's representative PC Chang - described by colleagues as the "towering intellectual" on the committee - are said to have worked tirelessly to introduce the Confucian concept of Ren (仁). The character combines "person" (人) and "two" (二), embodying the idea that we become fully human only through our relationships with others, through compassion and co-humanity.

Chang understood something profound: after the atrocities of World War II, the problem was not the absence of 'rights' concepts, but that perpetrators had lost their humanity - their capacity to feel for victims as human beings. He proposed that the Declaration emphasise humanising humanity, cultivating emotional and existential connections between people rather than merely cataloging individual entitlements.

His Western colleagues were not interested. Eventually it ended up as "conscience", at odds with Ren's relational foundation - Chang as sophisticated diplomat eventually chose compromise over confrontation. The British representative also suggested "brotherhood" would suffice. Later, when the Declaration was translated into Chinese, Ren was not even included in Chang's own language, supplanted by Western political terminology.

Just consider the following: The concept of 'rights' proved so foreign to Chinese and Japanese that 19th-century translators struggled for decades to find equivalents. They eventually settled on quanli (權利) - "power and interest" - which perfectly captures rights' self-regarding (selfish) nature. Ren, by contrast, has no English equivalent because Western languages have no framework for its relational, duty-based conception of humanity.

This asymmetry tells you everything about whose concepts get globalised and whose get erased.

This was not just semantic quibbling. It represented the complete erasure of an alternative framework for human dignity, one that would have been based on duties, relationships and collective wellbeing rather than on individual rights and self-interest.

I quoted here from the September 2025 post in China21 Journal; and you can find much more detail about the drafting of the UDHR in this article.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), 1948

The UDHR covers a broad spectrum of rights. The Foundational Principles are captured in Articles 1-2 - human dignity, equality and non-discrimination. Civil and Political Rights are reflected in Articles 3-21 - life, liberty, and security; fair trial; freedom of movement; asylum; marriage and family; freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; freedom of opinion and expression; peaceful assembly and association; political participation; and so on.

It is perhaps no accident that these civil and political rights are mentioned early on in the Declaration, given Western dominance in its shaping. It is largely these rights that are weaponised - selectively held up to the Global South or used as excuse to evade or sanction uncooperative countries.

The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights follow next in Articles 22-27 - social security; work and fair wages; rest and leisure; adequate standard of living (including food, housing, healthcare; education); and participation in cultural life.

Framework Articles 28-30 conclude the Declaration - the right to a social order where rights can be realised; duties to community; and limitations only for securing others' rights.

While all these rights are presented as equally fundamental and interconnected, debates persist about implementation priorities and whether certain rights enable others. This is clearly rooted in the deeply embedded philosophical differences that determine the psyche of societies.

What the World Actually Needs

In specific cultures, such as some in the West, human rights are treated as separate from economic, social, and political factors and are viewed primarily as legal and moral concerns. This separation makes it easier to frame human rights issues through emotional appeals and absolutist principles. In contrast, China's more diffuse perspective integrates human rights with broader socioeconomic conditions, prioritising rights related to housing, education, and employment as fundamental rights to well-being (as defined in UDHR). - George Dumoulin, Peter Peverelli

Here is a fact that should inspire every human rights advocate: China has lifted over 800 million people out of poverty in forty years, widely and authoritatively acknowledged as the single greatest poverty reduction achievement in human history, likely never to be repeated.

That is more than freeing the entire population of Europe from destitution.

If human rights mean anything, surely the right to eat, to have shelter, to access healthcare and education must come first!

And China is not alone in its massive contribution to human rights. Countries like Ethiopia, Rwanda, Vietnam and Bangladesh each has their own impressive success stories despite efforts to paint a different picture. These countries have each done more for human rights in the Global South than the whole of the rich Global North since colonisation (itself an incredible abuse of human rights).

These nations understood what the West refuses to acknowledge: rights without development are meaningless abstractions.

You cannot eat freedom of assembly. You cannot house your family with freedom of the press.

More about this in Part 2.

Member discussion