Titbits and Snippets 3. Modernising on Our Own Terms

It sticks in my mind. The AU official who asked me whether "Made in Africa Evaluation" (MAE) might mean we will be moving backward rather than forward.

Ken Opalo's brilliant-as-usual recent post about Ethiopia's lagging development since the 1900s reminded me again of this incident, which happened when I was facilitating a series of sessions on MAE at CLEAR-AA in Johannesburg some years ago.

To me the AU official's comment personified the lack of knowledge and pride among many Africans about their own histories and cultures. Understandably so, given that colonisation has done its best to erase Africa's often impressive history and identity. It is hard to cultivate again, but Rwanda sets a good example of how to do it. And it is already more than 50 years after the end of most of the settler-colonialism in Africa.

But the official's comment also personifies the scourge of 'aid thinking'. We cannot blame aid for the fact that we too easily and comfortably come to rely on foreigners. Opalo notes the critical mistake by Ethiopia's famous emperor Haile Selassie:

"Instead, he chose a schizophrenic existence of mostly outsourcing the modernisation drive (and thinking behind it) to foreigners, while clinging to traditional sources of power and authority."

And quoting from Kebede, he notes:

"On the severe material and human shortcomings was grafted an educational policy that lacked direction and national objectives. According to many scholars, the main reason for the lack of a national direction is to be found in the decisive role that foreign advisors, administrators, and teachers played in the establishment and expansion of Ethiopia's education system. That the curriculum tended to reflect at all levels courses offered in Western countries was a glaring proof of their harmful influence. As one author puts it, 'appointed foreign advisors tended to think that what had proved successful in their countries would also benefit Ethiopian development'."

This continues on the continent of course, aided by many of the African intellectual and political elites educated in grand Western universities.

This is particularly galling since we know that what the world needs today are the ancient wisdoms and practices that long ago typified Asia (including West Asia), Africa, and Indigenous peoples on other continents - albeit tailored for modern times.

There is nothing new about holism, (eco)systems or complexity thinking, harmonising the interests of people and nature, a spiritual view of the world, and so on. These were the values and practices that Western dominance and the scientific paradigm intentionally and unintentionally destroyed.

But then of course, the other key argument, which Opalo articulates so well in his post:

"From an African perspective, it follows that the way to correct the accumulated mistakes of history on the Continent cannot be the standard perennial moralising in the hope of changing foreigners' character; while using Africans (cast as noble victims of history, of course) as a foil in self-indulgent political projects. Instead, what's needed is a fair amount of internal reflection regarding when and why the proverbial rain started beating the region, followed by investments in the means of maximising African agency on the world stage. That is the only way that African states and societies will be able to thrive on the grand stage of history on their own terms, and not predominantly feature as side plots in others' history."

This is why some of the new generation of African leaders like Ibrahim Traore as well as the growing group of young, well educated, inspiring Africans proud of their heritage - and some older ones too - give us hope, in spite of knowing that it will be an uphill struggle to change continent-wide. Opalo again:

"There is no deep mystery about political and economic underdevelopment on the African Continent. At a fundamental level, the story is one of repeated failures at critical junctures of history to develop mechanisms of organising and protecting productive economic activity at scale. The resulting lag relative to other regions then yielded compounding effects over time. And in my view, the biggest driver of these regional failures to keep up has been the absence of historical self-awareness among Africa's ruling elites. This reality has resulted in elites losing hegemonic legitimacy vis-a-vis their own people, having diminished agency on the world stage, and totally lacking in ambition. Given their important role in coordinating collective action and enforcing the norms that animate institutions, it's impossible to go far with low-ambition elites."

He concludes:

"In order to create an enabling environment for their people to flourish and to safeguard African agency on the world stage, African societies must focus on rapidly and unapologetically modernising on their own terms. It is as simple as that."

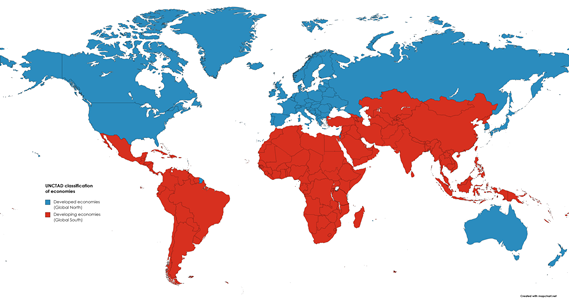

Modernising on our own terms - blending the best from the rest with the best of our own. And we have examples, primarily from China and a few other countries in East who did not follow Western beliefs and prescriptions about 'development', or create dependencies on aid.

China's case is particularly remarkable, given that it is the most successful story in history of lifting people out of (extreme) poverty, and developing rapidly economically, technologically and societally too. It did blend good ideas and practices from elsewhere into its way of working; it still does not shy away from learning from others it deems worthwhile. But where it does so, it blends and adapts and innovates rather than duplicates. And it develops on its own terms. Rather than copying for example the Washington-Consensus playbook of shock privatisation and full market liberalisation, China has spent 40 years relying on state-directed, trial-and-error reforms - "crossing the river by feeling the stones" - that combined gradual opening, mixed ownership, heavy public investment and systematic long-term planning based on a deeply embedded systems view of the world, further informed to a greater or lesser extent by other aspects of Daoist (especially), Buddhist and Confucian philosophies.

This adaptive, government-led model, sometimes dubbed the 'Beijing Consensus', let Beijing steer capital, technology and policy sequencing on its own terms, powering rapid growth without adopting Western institutional frameworks - albeit initially sacrificing the environment in the process, but now rapidly turning that around.

No wonder the shrill voices of propaganda against China has become deafening. Expect more as it continues to refuse to bow.

See the rest of Ken Opalo's post about Ethiopia here.

Member discussion